Creative Commons

From Kristallnacht and Back: Searching for Meaning in the History of the Shanghai Jews

Kevin Ostoyich

Valparaiso University

Prof. Kevin Ostoyich was a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2018 and was previously a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2017. He is Professor of History at Valparaiso University, where he served as the chair of the history department from 2015 to 2019. He holds his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and his A.M. and Ph.D. from Harvard University. Prior to moving to Valparaiso, he taught at the University of Montana. He has served as a Research Associate at the Harvard Business School and an Erasmus Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently is an associate of the Center for East Asian Studies of the University of Chicago, a board member of the Sino-Judaic Institute, and an inaugural member of the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum International Advisory Board. He has published on German migration, German-American history, and the history of the Shanghai Jews.

While at AICGS, Prof. Ostoyich conducted research on his project, “The Wounds of History, the Wounds of Today: The Shanghai Jews and the Morality of Refugee Crises.” The Shanghai Jews were refugees from Nazi Europe who found haven in Shanghai, and thus escaped the Holocaust. For this project Ostoyich has interviewed many former Shanghai Jewish refugees and has conducted research at the National Archives at College Park, MD, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At Valparaiso University he co-teaches a course titled “Historical Theatre: The Shanghai Jews,” which fuses the disciplines of history and theatre. To date, students of the course have co-written and performed two original productions based on the history of the Shanghai Jewish refugee community: Knocking on the Doors of History: The Shanghai Jews and Shanghai Carousel: What Tomorrow Will Be. In addition to his work on the Shanghai Jews, he is currently working on projects pertaining to the experiences of ordinary Germans during the bombing of Bremen, German Catholic experiences in nineteenth-century Württemberg, German Catholic migration, and U.S.-German cultural diplomacy during the first half of the twentieth century.

Click here for an article by Ostoyich on the Shanghai Jews.

He is currently trying to interview as many former Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

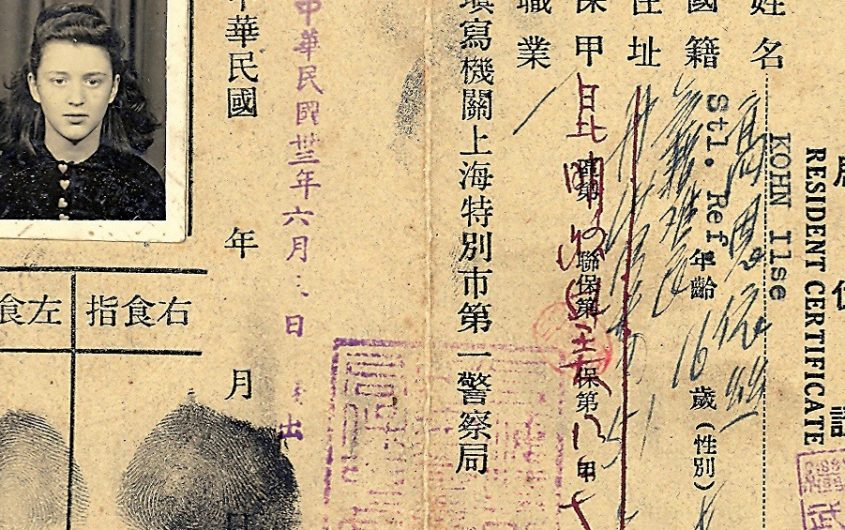

When the Jews sought refuge from the Nazi regime, they were most often met with hatred and indifference. Most of the world closed its doors on the Jews, and, for that reason, Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist regime were able to perpetrate the worst horror in human history: The Holocaust. Fortunately, approximately 18,000 to 20,000 Jewish refugees were able to find haven in Shanghai, due to the fact that an entry visa was not needed to land there. Most of the refugees had been stripped of most, if not all, of their belongings. A number of them had spent time in concentration camps. Once in Shanghai the Jewish refugees began their lives anew, creating their own community, with newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts, operettas, vaudeville, theater, sports teams, cafés, and clubs. Just when the refugees were getting back on their feet, however, the occupying Japanese forced all “stateless persons” who had entered the city after January 1, 1937 (i.e., the Jewish refugees from Europe) to move into a “Designated Area” (often referred to as the “Shanghai Ghetto”) in Hongkew, the poorest section of the city. Within the Designated Area the Jews found themselves subjected to extremely poor sanitary conditions, a significantly decreased food supply, and constant humiliation at the hands of the Japanese authorities. After the conclusion of the Second World War, the Jews left Shanghai. On May 27, 2017, Harry J. Abraham, the founder and president of ProQuip, Inc. of Macedonia, Ohio, sat down in his home in Moreland Hills, Ohio, and reflected on his refugee experience in Shanghai. For Harry the meaning of the ordeal that he and other refugees endured is to be found in shards of glass…

Read the stories of other Shanghai Jews

From Kristallnacht

The shards of window glass fell upon the sleeping infant. A brick had been thrown through a window of the Abrahams’ home on the night of November 9-10, 1938. That night and that glass still cut deeply in the mind of the now 79-year-old Harry J. Abraham. Kristallnacht (“Night of Broken Glass”) marked a turning point in the persecution of the Jews; it also marked a turning point for the Abraham family. On that night, Harry’s father, a cattle trader, was not with the family in Frickhofen, but away on business in his hometown of Altenkirchen. He was forcibly taken to the Market Square and then sent to Buchenwald concentration camp. In retaliation for the shooting of a German official by a Jewish youth in Paris, the Nazis had unleashed this orgy of hatred and destruction. Throughout Germany synagogues were burned and Jews beaten. The toll was staggering, with scores of synagogues destroyed, over 7,000 businesses trashed, approximately 30,000 Jews arrested, and upward to 100 killed. (Those wishing to learn more about the atrocities committed on that night and in the days that followed should visit the interactive website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.) In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the regime intensified its efforts to strip Jews of their belongings and kick them out of the country. Those like Harry’s father and uncle, who found themselves in a concentration camp, were told they would be released only if they presented proof of passage out of Germany. At this point an unlikely destination presented itself to the Abraham family. Harry’s maternal grandfather, who had served in the German Navy during the First World War, heard that Jews were fleeing to Shanghai and informed Harry’s mother about this option. She immediately purchased tickets for Harry’s father and uncle. Having secured proof of passage, the two men were released from Buchenwald. They boarded a train from Frankfurt to Genoa and took a steamship from the Italian port to Shanghai. Harry’s “very determined” mother then purchased tickets for herself, Harry, and her parents. Having no interest in journeying halfway across the globe and thinking everything would blow over, her parents refused to go. Thus, in April 1939, mother and infant son journeyed from Genoa to Shanghai aboard the Italian steamer Conte Biancamano. When mother and son joined father and uncle in Shanghai, they were by no means alone. Following Kristallnacht thousands of Jews fled to Shanghai—not for the sake of adventure, but out of sheer necessity. Shanghai was the last haven of hope as the world closed its doors on the Jews.

The Abraham family entered a city with deplorable housing, rampant disease, and abysmal sanitation. Most of the refugees arrived after most, if not all, their belongings had been “aryanized” (either confiscated outright or forcibly sold at a fraction of the value) and what little had been left, spent on their journey to Shanghai. Many possessed little more than the clothes on their backs. The refugees were greeted at the docks and transported on trucks to homes or barracks which provided meals sponsored by Jewish charitable organizations and lodgings bereft of privacy. Given how young Harry was when he and his mother arrived in Shanghai, he does not remember much of the first years there. His memories are of the time well after the Japanese asserted full control of the city in December 1941, subsequent to the attack on Pearl Harbor and after the occupying Japanese forces decreed in February 1943 that all “stateless persons,” who had arrived after January 1, 1937, had to live in a Designated Area in the depressed Hongkew district of the city. Ever since the proclamation of this decree, the Jews referred to the Designated Area as a ghetto; Harry refers to it simply as “the camp.” The Designated Area was technically neither a ghetto nor a concentration camp; it was not walled off and it was not exclusively inhabited by Jews. Chinese actually far outnumbered Jews in the Designated Area. Nevertheless, the Jews had been stripped of their freedom, and conditions were deplorable. The refugees had to obtain passes from Japanese officials in order to leave the Designated Area for any purpose. As the war progressed, conditions deteriorated considerably, with disease and hunger running rampant.

In Shanghai, Harry’s family lived in an apartment building with many other families. His father continued to work as a trader. Being quite resourceful, he developed a business that consisted of buying the tin cans refugees received in care packages and then selling them to the Chinese, who used them for gutters and stove pipes. The business flourished, and Harry’s father accumulated burlap sacks full of cash. The only problem was the war inflation made cash basically worthless. Meanwhile, Harry’s mother used the Singer sewing machine her grandmother had given her and which she had brought on the journey from Frickhofen to make clothes. Harry jokes that one time his mother must have forgotten he was a boy when she made his pajamas because she had sewn the buttons on the wrong side!

Harry attended a school in Shanghai that was supported by the Jewish community. The school had a couple hundred students and went until the early afternoon. Afterward, Harry would attend Hebrew school under the direction of the Mir Yeshiva. The members of the Mir Yeshiva escaped from Lithuania to Shanghai via Siberia and Kobe, Japan. Because of Shanghai, the Mir Yeshiva was “the only eastern European yeshiva to survive the Holocaust intact.”[1] Harry remembers his schooling to have been quite rigorous and conducted exclusively in English. Thus, while parents spoke German, the refugee children often spoke English. Sometimes the Jewish children would play with Chinese children, but overall, the interaction between Jews and Chinese was minimal. Interactions with Japanese was limited mostly to officials making clear to the refugees “in no uncertain terms […] what the rules were.” Like most other refugees, Harry never learned to speak Chinese. The aim was to learn English.

Toward the end of the war, the Americans bombed Shanghai. Harry remembers well Japanese enforcing strict blackout procedures and his family taking shelter during air raids. One day in particular—July 17, 1945—would etch itself into the memories of the Shanghai Jews. On that day, American bombers accidentally struck the Designated Area. It was horrific. Just a few weeks later the Americans bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Harry distinctly remembers news of the atomic bomb finding its way into the Designated Area. His parents talked about it, and in school children were told that “something had happened that was very, very terrific and very costly in human lives in Japan.” The Japanese surrendered and the refugees celebrated. The streets were jammed with yelling and cheering refugees, and at school the next day the end of the war was the topic of discussion. Harry remembers everything instantly feeling “open.” People started buying ice cream. Whether it was real ice cream—perhaps “it was ice milk or something or other”—did not matter; “it was good.”

The refugees started to plan where to go next. As was common, Harry’s family never viewed Shanghai as a permanent home. Their goal always had been to go to some English-speaking country, perhaps Australia, South Africa, or the United States. Given that Harry’s father had two brothers in the States—one of them serving in the U.S. Army during the war—the United States was the top choice. The lore of the United States only grew when American G.I.s arrived immediately after the war. Harry and his schoolmates put on a play and sang for the G.I.s, and in return the G.I.s taught the children how to play Monopoly.

Harry’s family traveled on a troop carrier, the USS General M.C. Meigs, from Shanghai to San Francisco via Yokohama and Honolulu. From San Francisco, they traveled on to Pittsburgh, where his mother found a job. Shortly thereafter, during a Thanksgiving visit to family in Cleveland, Harry’s father went to the “Gates of Hope” Synagogue, which had been established by German-Jewish refugees during the early 1940s. There he encountered one of the owners of Campus Sports World, who offered him a job in Cleveland; thus, the family moved from Pittsburgh to Cleveland.

Back to Kristallnacht

Although Harry’s English was initially not on the level of other children his age, he soon encountered friendly people who helped him. His family lived in a community that was roughly half white and half black. Harry quickly became integrated in the black community, primarily making friends through baseball. As had been the case in Shanghai, Harry continued to attend Hebrew class after school. Although not totally observant himself, Harry’s father felt it important that Harry continue to observe Judaism. As Harry looks back now, he is particularly struck by how little the issue of what had happened to the Jews—even the gas chambers—was discussed. Few people seemed interested in this history. Harry, however, had questions. He would ask his father, “Why did you stay in Germany?” Not wanting to talk too much about such matters, his father simply said that in 1933 people just did not see what was going to happen. He explained that in the beginning the people—even Jews—supported Hitler because they thought he would be good for the country. Harry could not figure out why his father and others had not been able to see through Hitler from the very start. His thoughts ultimately led to a fundamental question: What in human nature would allow something like Kristallnacht to happen? Put another way: What makes people indifferent to injustice? To Harry this question should guide any investigation of the Holocaust. It pains him that such questions often go unasked when the Holocaust is commemorated. Instead studies tend to focus exclusively on experience. This focus on historical experience can often stifle questions and obscure history’s underlining meaning. The narrative should never lose sight of the action or inaction that allowed the experience to transpire in the first place. Although Harry makes a clear distinction between the history of the Shanghai Jews and the Holocaust and believes anyone who equates the two is simply “wrong,” he does believe the commemorations of both histories fall prey to the same pitfall. To Harry, the Shanghai experience itself was not that historically significant; after all, it was just a small group who stayed in Shanghai for a relatively short period of time, he says. This changes, though, if one were to “talk about it and present it in the context of Kristallnacht or something that forced that situation. That, that […] is important.” The fact that the Jews were able to live in Shanghai is also significant. He believes that both the Chinese and the Japanese deserve respect. He knows there were instances of unpleasant dealings between the Jews and the Chinese and Japanese in Shanghai, but in the end, “They allowed us to survive. […] They could have shut the door, and we wouldn’t be talking today.”

Why did the Jews have to flee halfway across the world in order to survive? This question and its relationship to Kristallnacht continues to plague Harry’s thoughts. Why did people not stand up when concentration camps were set up in German towns and friends were being sent to them? Harry posed this question to his father’s former friends when he traveled to Altenkirchen years ago to see how graves of family members were being tended. After having been interviewed by a German newspaper reporter in the presence of his father’s former friends, Harry asked some questions of his own:

I started to ask [the] question; they started to cry. They were crying. They said, “We didn’t know anything about this.” Because, you know what I asked them? I said, “How could you let my father go to Buchenwald? How? You were there. What did you do about it? At that time?” […] One guy said, “[Your father] was my best friend. I knew him as a Jew, but he was my best friend.” [I responded,] “How then could you let him go?” And these were people in the town that knew my father [who] were allowing this to happen. A simple question. They had no answer for me. “We didn’t know. We didn’t understand.” They started to cry.

Belated tears are meager answers. Harry reminds us that we need to continue to ask the question “why” with respect to the Shanghai Jews, the Holocaust, and Kristallnacht. When one goes back to Kristallnacht, one is confronted with the capacity of man to remain indifferent to the persecution of others. The history of the Shanghai Jews should always return to this point. Commemorations of experience should always lead back to the question “why?” Why, for example, did the Abraham family have to journey so far to survive? In Germany, there should have been more of a response to a cow trader being rounded up with others in a market square; there should have been more of a response to life-long friends being sent to concentration camps for no other reason than their being Jewish; there should have been more of a response to glass falling on a slumbering infant; there should have been, but there was not. Although the glass of Kristallnacht has long since been swept away, questions regarding humanity’s capacity for indifference continue to cut deeply.

[1] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Mir Yeshiva.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007090. Accessed on August 1, 2017. For more information on the Mir Yeshiva in Shanghai, see David Kranzler, Japanese, Nazis & Jews: The Jewish Refugee Community of Shanghai, 1938-1945 (Hoboken, NJ, 1988), 431-435.

Professor Kevin Ostoyich’s research on the history of the Shanghai Jews is being sponsored by a research grant of the Sino-Judaic Institute and the Wheat Ridge Ministries – O.P. Kretzmann Memorial Fund Grant of Valparaiso University.