Should Germany Go Nuclear?

Stephen F. Szabo

Senior Fellow

Dr. Stephen F. Szabo is a Senior Fellow at AICGS, where he focuses on German foreign and security policies and the new German role in Europe and beyond. Until 2017, he was the Executive Director of the Transatlantic Academy, a Washington, DC, based forum for research and dialogue between scholars, policy experts, and authors from both sides of the Atlantic. Prior to joining the German Marshall Fund in 2007, Dr. Szabo was Interim Dean and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and taught European Studies at The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. He served as Professor of National Security Affairs at the National War College, National Defense University (1982-1990). He received his PhD in Political Science from Georgetown University and has been a fellow with the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and the American Academy in Berlin, as well as serving as Research Director at AICGS. In addition to SAIS, he has taught at the Hertie School of Governance, Georgetown University, George Washington University, and the University of Virginia. He has published widely on European and German politics and foreign policies, including. The Successor Generation: International Perspectives of Postwar Europeans, The Diplomacy of German Unification, Parting Ways: The Crisis in the German-American Relationship, and Germany, Russia and the Rise of Geo-Economics.

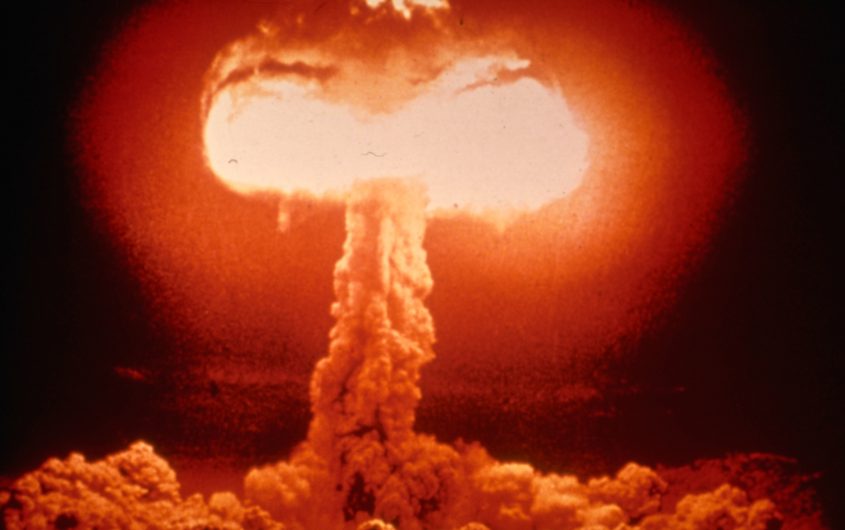

Should Germany go the route of France and the UK and develop its own independent nuclear weapons capability? Something which once seemed unthinkable is now back in the political discussion in Berlin. The distinguished political scientist Christian Hacke published an op-ed in Welt am Sonntag (in English here) this past weekend arguing “Germany’s new role as enemy number one of the American president forces Germany to a radical rethinking of its security policy.” He went on to argue, “The Federal Republic of Germany is for the first time since 1949 without the nuclear umbrella of the United States. Germany is defenseless in case of an extreme crisis.” Hacke is not alone in raising this issue. The leading defense expert of the Christian Democrats in the Bundestag, Roderich Kiesewetter, made this case two years ago. Alexander Graf Lambsdorff, the vice chair of the Free Democrats and its leading foreign policy expert, agrees that German policymakers must openly discuss this theme: “The end of the Cold War did in no way end the era of atomic weapons—one can lament this but that is the reality.”

There are many reasons to believe that an independent German deterrent will not come about and the reaction of Wolfgang Ischinger and others in the foreign policy establishment make those clear. First are treaty commitments including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Two Plus Four treaty ending the division of Germany, both of which renounced the national control of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. As Ulrich Kühn and Tristan Volpe have contended, the planned phase-out of nuclear power makes a restarting of a military program difficult and very costly. While Japan and Iran could go nuclear quite quickly, this would not be the case for Germany.

If a future German government were to renounce these obligations it would reopen the German Problem and lead to an escalation of tensions not only with Russia, but with Berlin’s European partners. Would a Polish bomb be far behind? Germany would once again face encircling alliances. There is also the domestic political context. Only the Alternative for Germany (AfD) would openly welcome such a move; the reaction from the other parties and the public would be overwhelmingly negative. Chancellor Merkel’s policy to close all nuclear power plants has been widely supported and reflects a deeply anti-nuclear and anti-nationalist public.

What is important about this new debate is that it signals what Wolfgang Ischinger has called the beginning of the shaping of a Plan B for Germany in a post-American world.

What is important about this new debate is that it signals what Wolfgang Ischinger has called the beginning of the shaping of a Plan B for Germany in a post-American world. The German foreign policy establishment has hoped to avoid this for the understandable reason that there is no immediate alternative to reliance on the American deterrent. However, President Trump and large elements of the Republican Party have now undermined the credibility of that deterrent and seem to be closer ideologically to Putin than to Merkel. In fact, as President Trump has made clear, he favors national nuclear forces in Japan and South Korea as a means of freeing up America from its defense commitments.

What would this Plan B look like? The short answer is a new Harmel formula, the doctrine named for a Belgian foreign minister and adopted by NATO in the 1960s under German leadership, directed at the Soviet Union which combined détente and defense. That is what Germany must now do vis-à-vis both Putin’s Russia and the Trump administration. In regard to the nuclear issue, it should follow the advice of Ischinger, Kiesewetter, and others and bolster Germany’s defense capabilities to make it less reliant on the U.S. for its conventional defense while enhancing European defense cooperation. Hacke makes a strong case for doing this in his article and he is right to urge that the German strategic community get serious about the new threat environment Germany faces—to include the reestablishment of conscription.

Putin’s Russia poses more of a threat through corruption and information war than through nuclear confrontation.

In contrast, Hacke’s conclusions about the need for an independent German deterrent are unconvincing and rooted in Cold War concepts of deterrence. Russia could choose to use the threat of nuclear weapons on Germany and Europe to pressure concessions on issues of importance to Moscow, but the credibility of nuclear blackmail seems weak in today’s Europe. Russia is not the Soviet Union and it no longer has the Warsaw Pact in the center of Europe. Its conventional forces remain limited in their ability to project force far beyond its borders and have struggled in Ukraine. Putin’s Russia poses more of a threat through corruption and information war than through nuclear confrontation. Germany still has many economic levers to use on Russia, and France maintains the nuclear option as a backup to European conventional defense. Hacke dismisses the credibility of the extended deterrence of a European or French nuclear force, quoting deGaulle that, “Nuclear power is difficult to divide.” However, French doctrine is now necessarily European given the weakness of the American guarantee. Germany is not limited by the NPT or the Two Plus Four treaty from cooperating with a European deterrent and should explore ways to work more closely with France toward this goal, including helping to finance French nuclear modernization as Ischinger, Kiesewetter, and others in Berlin advocate.

Berlin and Paris should also work with Poland and the Baltic states to find ways of making a European stabilization force more visible in eastern Europe. Would Russia be any more likely to risk killing French, German, and Polish troops than Americans? All these steps along with the economic diplomacy of both Germany and the EU should provide for a more independent Europe able to now resist both Moscow and Washington. This would also provide leverage for détente on issues of common concern. What is essential is that German leaders now make a convincing case to their public for the vital German national interest in a more robust and serious German military capability, not because it pleases the American president, but because it is the means to resist him. As in the past, a Europeanization of German policy is far more effective than a purely national approach. As Washington is learning, “America First” means America Alone. The same would apply to a Germany First nuclear policy.