Photo by author

The Afghanistan War: Collective Memory Formation in the United States and Germany

Axel Heck

Kiel University

Dr. Axel Heck is a DAAD/AICGS Research Fellow from May to mid-July 2019. He is a senior lecturer in International Relations at Kiel University in Germany. Prior to his appointment in Kiel, Dr. Heck was a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Freiburg, research associate at the University of Mainz, and lecturer at the University of Frankfurt. He received a graduate fellowship from the Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation for his PhD and he was a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University (SAIS) in Washington, DC. Dr. Heck is the author of Macht als soziale Praxis: Die Herausbildung des transatlantischen Machtverhältnisses im Krisenjahr 1989 (Power as social practice: the formation of the transatlantic relationship in the crisis of 1989) on power in transatlantic relations and several articles on representations of war in media, culture, and society.

During his fellowship at AICGS, Dr. Heck will compare collective memory formation regarding the Afghanistan war in Germany and the United States.

Introduction

More than eighteen years have passed since October 2001, when U.S. forces were deployed to Afghanistan after the Taliban regime refused to extradite Osama bin Laden and shut down Al-Qaeda terror camps. Even today, the war in Afghanistan is inseparably linked to the memories of 9/11 and the Al-Qaeda mastermind. When U.S. Special Forces killed bin Laden in Pakistan in May 2011, people all over the United States were relieved. Citizens came together in front of the White House in Washington, DC, in Times Square in New York City, and across the U.S., cheerfully shouting: “U-S-A, U-S-A” or “Obama killed Osama”—a slogan that was even printed on t-shirts.[1] Moments when Americans are united in such celebrations have become rare. Moments when politicians from both sides of the aisle unanimously congratulate a sitting president are even rarer. The wounds 9/11 has left behind in the U.S. public consciousness are deep, and the ongoing war in Afghanistan is a constant reminder. But practices of collective remembrance and celebrations help people to deal with these wounds and to reaffirm national identity, in spite of political differences and controversies.

Practices of collective remembrance and celebrations help people to deal with these wounds and to reaffirm national identity, in spite of political differences and controversies.

When bin Laden’s death hit the news, German chancellor Angela Merkel said in a press statement, “Ich freue mich darüber, dass es gelungen ist, bin Laden zu töten,” which means that she was “pleased” or “delighted” that he had been killed. Merkel’s rather unusual emotional wording caused an immediate public outcry. Labels of “clumsiness” and “inappropriateness” were among the weaker reactions; a judge from Hamburg even filed a charge of “public endorsement of a criminal act” (which is punishable in Germany), and called her expression “beyond all values,” as Der Spiegel reported.[2] Harsh reactions to Merkel’s statement on bin Laden’s death indicate that people in Germany and the United States not only hold a slightly different perspective on how to deal with the perpetrators of 9/11, they remember and or commemorate such incidents collectively in very different ways. In Germany, the public celebration of such a killing—even of a top terrorist—is beyond imagination.

The United States and Germany are bound together by thousands of family ties, friendships, and professional relationships. People in both countries are more similar than often assumed. But the two nations differ enormously regarding their national identities and their self-understanding as actors on the global stage. Hence, one could expect that the collective memory of war also works quite differently.

The United States is a military superpower, in possession of the most expensive and technologically advanced military machinery. According to SIPRI, the United States is responsible for approximately one-third ($684.8 billion) of world-wide military expenditures, followed by China ($250 billion) and Saudi Arabia ($67.6 billion).[3] In U.S. foreign policy, the use of military force has been considered a necessary tool to protect national interests and to exercise power—recent claims by Senator Lindsey Graham and others to punish Iran militarily for the Houthi drone attack on Saudi Arabia are the rule, not the exception.[4] The president is the Commander in Chief and has the prerogative to deploy forces without congressional approval if national interests are threatened. Many people in the United States have opposed war in the past—from the engagement in the Second World War to Vietnam to Iraq. But there is no general suspicion or objection in society against the use of military force as an instrument of foreign policy.

In Germany, the situation couldn’t be more different. Due to the devastating experiences in the first half of the twentieth century and Germany’s position at the front line of the Cold War, the use of military force and even talking of “war” is poisoned—even today. Given the limited sovereignty during the Cold War, the deployment of the Bundeswehr was politically unthinkable and strictly limited by the constitution. This changed with the transformation of the world order and NATO in the 1990s—some people might remember Richard Lugar’s NATO phrase “out of area or out of business”—and the German Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe’s decision to change the conditions for the deployment of the Bundeswehr.[5] But one major hurdle remained: troop deployments need approval by the parliament. As a result, whenever the use of force is considered by the government, a heated public and parliamentary debate emerges. The discussion in the Bundestag is more than democratic “window dressing”—troop deployment is a core right of the legislative branch and taken very seriously. This became very obvious when the Bundestag decided to send armed forces to Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks.

Today, more than eighteen years after troops were first deployed, it is unclear how the Afghanistan war will be remembered in both countries. Regarding the different national identities in terms of the self-understanding as military actors on the global stage, one could expect different memory cultures, practices of commemoration, and remembrance. But due to the fact that both countries were engaged in the same war with an all-voluntary army, fighting side-by-side in many operations, one could also expect similarities in the way the Afghanistan war will be remembered not only by practitioners and experts, but also in society at large.

The Afghanistan War and Collective Memory

U.S. Engagement in Afghanistan

More than 2,400 U.S. soldiers have been killed during the war in Afghanistan. Thousands returned injured and suffer from ongoing physical and mental wounds. In financial terms, the war has cost American taxpayers about $1 trillion. If the Trump administration maintains current levels of approximately 15,000 soldiers, each additional year will cost roughly $35 billion. Although there was initial consensus on the justification of the Afghanistan war, public approval has dropped dramatically since 9/11. Today, nearly 50 percent of Americans see U.S. involvement as a failure.[6] According to a recent Pew report, only about 36 percent of people say it was worth fighting the war in Afghanistan. Among veterans, that number is only marginally higher, at 38 percent.[7] Of course, there are demands to bring home the troops and to end the war. As there is no draft, those opposed to the war are not sufficiently galvanized to protest or mount large-scale campaigns. Without such efforts, the situation is not comparable to the opposition to earlier wars, for example, in Vietnam. In sum, although the vast majority does not support an ongoing military presence in Afghanistan, they can live with it.

Practices, Ceremonies, and Memorializing Events in the U.S.

In the United States, the armed forces hold a special status within society. Memorial Day—the last Monday in May—is dedicated to those who have lost their lives as military service members, while Veterans Day—November 11—honors all military veterans. On Memorial Day, people commemorate and remember fallen soldiers at memorials across the country, and flags are planted in front of the tombstone of each veteran. In Washington, DC, Memorial Day weekend has had a special flair; thousands of bikers from across the United States find their way to the capital to celebrate the “Rolling Thunder”[8] parade and other services take place, including at the Marines Memorial and the Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, VA, and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall.

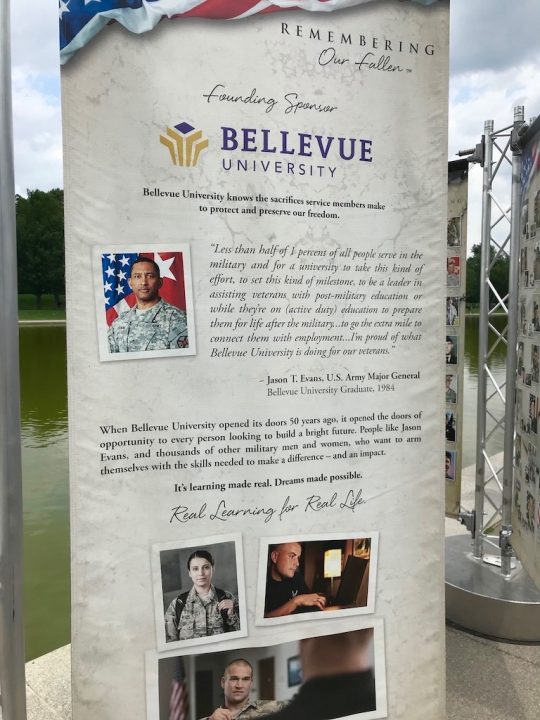

Memorial Day is non-partisan and patriotically-charged. But neither Rolling Thunder nor the official Memorial Day parade are dedicated to U.S. wars. They are staunch celebrations of the individual veterans who served their country. Nevertheless, the holiday serves as a platform for organizations to highlight the impacts of particular wars.

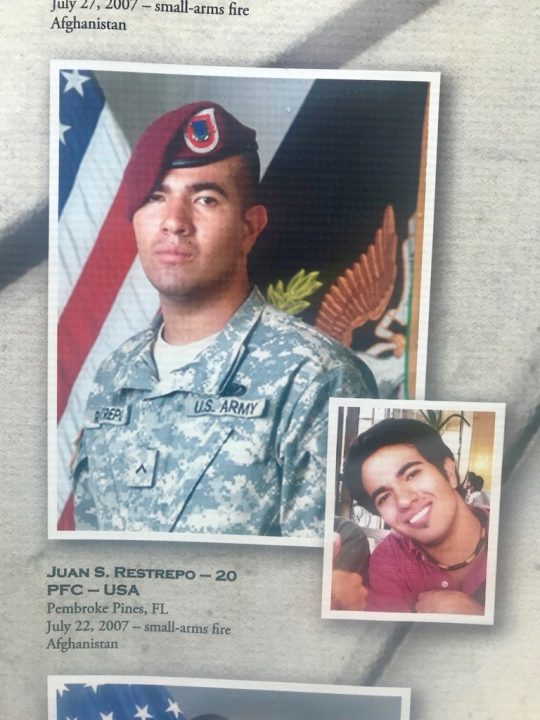

During my research stay at AGI in spring 2019, I had the opportunity to observe that year’s Memorial Day commemorations. The organization “Remembering Our Fallen” presented the most impressive reference to Afghanistan and the war in Iraq. They placed posters along the Reflecting Pool on the National Mall portraying more than 8,000 soldiers who were killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. These posters show images of the soldiers, mostly in uniform, and provide some basic information such as names, rank, city of birth, and where, when, and how they were killed. These photos of primarily young adult soldiers are powerfully contrasted with more casual pictures of them with family and friends, or as children. The visual juxtaposition of the professional soldier in military portrait and the private photos is emotionally touching as it humanizes the fallen.

One photo, in particular, caught my attention: Private First-Class Juan S. Restrepo, who was killed at the age of 20 in the Korengal Valley, Afghanistan. “Restrepo” is also the title of a 2010 documentary film which, together with its sequel “Korengal,” is based on original video footage and interviews with U.S. soldiers, and directed by photojournalist Tim Hetherington and author Sebastian Junger. Hetherington and Junger joined the Second Platoon, Battle Company, of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, which was deployed to the Korengal Valley. Before Junger and Hetherington arrived in Afghanistan, Juan Restrepo was killed by insurgent fighters. Later, an outpost in the Korengal Valley was named “Restrepo” in his memory. By providing respectful but unprecedented proximate access to soldiers’ lives in combat, these documentaries uncover the futility and trauma of a seemingly endless war from the perspective of those experiencing it. In the film, Juan is shown joking with his friends about going to war, a young man unaware of what’s to come. “Restrepo” was internationally-acclaimed and received an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary film.

Spaces and Places of Memory and Remembrance

While “Restrepo” and other films keep the war in the (pop-) cultural memory of the United States, the Veterans Museum in Columbus, OH, employs a different approach. There, the U.S, wars and the service members who fought in them are remembered more formally. Opened in 2018, the museum broadly covers American war history. State-of-the-art museum pedagogy directs visitors chronologically through different times and eras of war-making and soldiering. Multimedia boxes provide background information, facts, and original artifacts, and put soldiers’ experiences at the center of attention. The focus of the exhibition is on the more distant past, but there is a section dedicated to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well. Afghanistan and Iraq are presented together under the heading “Responding to Terror.” The events of 9/11 are inseparably linked to the war in Afghanistan, and this connection is reinforced in the museum. Notably, the museum has dedicated a special section to Juan Sebastian Restrepo, and an abridged version of his story is highlighted. Juan Restrepo, it seems, might become one of those tragic heroes, a symbolic figure, etched in the collective memory of the Afghanistan war.

There is a keen interest in U.S. society to honor those who have lost their lives in the service of their country.

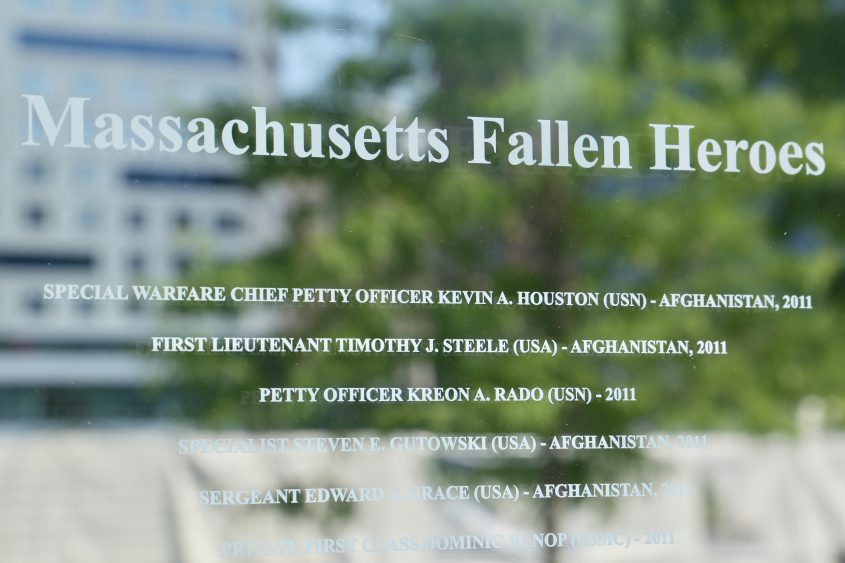

Besides the more formal and official memorialization in museums, there are countless private initiatives across the United States dedicated to soldiers who lost their lives in the line of duty. The U.S. Congress passed a bill paving the way for a Global War on Terrorism (GWoT) memorial in Washington, DC. In Boston, MA, a private initiative has built a memorial dedicated to the Massachusetts soldiers who died in Iraq and Afghanistan. These examples show that collective memory formation is driven by veteran associations and private engagements but also receives bipartisan endorsement. There is a keen interest in U.S. society to honor those who have lost their lives in the service of their country. It is also interesting to see that Iraq and Afghanistan are remembered together. Although many people frame these conflicts differently—some would dismiss Iraq as illegal and illegitimate, but also consider Afghanistan as a “right or “just” war—both will be remembered under the Global War on Terror narrative.

German Engagement in Afghanistan

During the eighteen years of war in Afghanistan, Germany and the Bundeswehr have experienced phenomena unknown since the end of the Second World War. Fifty-eight soldiers died in Afghanistan, 35 killed by enemy forces.[9] The first casualties occurred in 2003, when a suicide bomber targeted a German convoy, killing four soldiers en route to the Kabul airport.[10] While some observers awaited Germany’s departure from ISAF, the nation redoubled its efforts in Afghanistan—just weeks later, German commander Götz Gliemeroth took over ISAF command. In 2004, Germany further expanded its mandate and started to operate in Faizabad. In 2006, Germany took the lead of the Regional Command North and opened Camp Marmal in Mazar-I-Sharif.[11]

The German public was, for a long time, unaware of the situation in Afghanistan. Minister of Defense Peter Struck reminded the public that Germany’s “security is also defended at the Hindu Kush,” but the public believed German soldiers were more engaged in humanitarian assistance and building infrastructure.[12] When German newspapers reported the death of Sergej Motz, public awareness of the war in Afghanistan was low. Sergej Motz was the first German soldier who was killed during a firefight by enemy forces since the end of World War II.[13] The BILD newspaper reported that defense minister Jung attended his funeral, but deeper contemplation of the situation in Afghanistan took place only at the margins.[14] Today, only local newspapers from his home village in Swabia commemorate his death.[15]

Germany at War

German naïveté came to a sudden end when Colonel Georg Klein gave the order to bomb two hijacked fuel trucks south of Kunduz in September 2009. To date, the Kunduz airstrike is the most devasting attack in the history of the Bundeswehr, with more than 140 people killed, many of whom were civilians and children. “Kunduz,” as it is commonly known, shook German foreign policy like no other incident. Der Spiegel called it “a German crime,” referring to war crimes committed by the Wehrmacht.[16] Especially on social media platforms and blogs, Klein was called a “murderer,” though he has not been criminally convicted; several courts have dismissed indictments against him. “We have lost our innocence,” General Inspector Wolfgang Schneiderhahn later said in an interview with a German television broadcaster, in a docudrama about the incident. The political fallout was immense. Franz-Josef Jung was Minister of Defense when the airstrike happened and incorrectly claimed, shortly after the attack, that there were no civilian victims. He was proven wrong by a NATO report and forced to resign from the cabinet, despite having already left the defense ministry in favor of heading the labor ministry. His successor, new Minister of Defense Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, a rising star in the Christian Social Union (CSU), declared the attack militarily appropriate. After more facts came to light, he switched his wording to “not appropriate” and fired General Inspector Schneiderhahn and State Secretary of Defense Peter Wichert. A parliamentary investigation was implemented, and Klein declared in a hearing that he never intended to kill. By contrast, he said, the decision was proportional and in accordance with the mission he had to fulfill.

More than ten years have passed since the Kunduz airstrike and a lawsuit is still pending. Karim Popal, a lawyer for victims’ families, brought the case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg after all German courts dismissed the indictments against Klein and the Federal Republic of Germany.[17]

Several German newspapers ran stories about “Kunduz” on September 4, 2019, the tenth anniversary of the attack. Some of them directly addressed the issue of an “adequate” remembrance, which is complicated by split opinions about Klein’s decision.[18] Some people believe he is a murderer and should be charged; others feel he did the right thing given the difficult circumstances and limited information available. What is certain is that the Kunduz airstrike was a decisive moment in the history of the Bundeswehr and in German foreign policy. Although there is a tendency to collective amnesia when it comes to the war in Afghanistan, “Kunduz” remains in the public consciousness.

For the Bundeswehr, the war in Afghanistan went on, and turned bloody. On Good Friday 2010, thirty-four German paratroopers were ambushed in Isa Khel, close to the Kunduz camp. Taliban forces, supported by Islamist Uzbekistani fighters, engaged Germans in a firefight lasting upward of eight hours. Three German soldiers were killed, and eight more were severely wounded. The Good Friday Battle is the bloodiest hostile encounter in the history of the Bundeswehr, and it could have been worse—thanks to the temerity of a U.S. Black Hawk helicopter crew, the wounded German soldiers were safely evacuated. The fourteen U.S. Army aviators who braved a hot landing zone while under fire were awarded the German “Ehrenkreuz der Bundeswehr für Tapferkeit,” marking the first time the German cross of honor for valor was presented to soldiers of a foreign army.

Remembering the War in Afghanistan

Today, the Good Friday Battle is first and foremost remembered within the Bundeswehr. The incident is considered a “turning point,” responsible for “waking up” the public and politicians, and spurring the necessary equipment for this war. Unfortunately, two weeks later, the Bundeswehr was hit again. Four soldiers were killed when their vehicle veered off the road during an ambush. The Bundeswehr lost a total of seven soldiers in April 2010. From then on, even the German government referred to Afghanistan as “a war”—the poisoned term that had been avoided for so long.

The Bundeswehr has several places where soldiers and their families commemorate those who did not come back from Afghanistan. Most important in this regard is probably the Forest of Remembrance in Geltow, near Berlin.[19] At the site of the Henning-von-Tresckow barracks, the Bundeswehr has re-constructed the “Ehrenhaine” (memorials of honor) as they were present in the field camps in Afghanistan and other deployments. According to the project coordinator Lieutenant Colonel Bernd Richter the “forest” mainly addresses surviving soldiers and families who lost comrades and relatives in the war. But over the years an increasing number of people from broader society such as school classes come to visit the forest of remembrance as well.

Already in 2009, the “Ehrenmal der Bundeswehr” was inaugurated by Federal President Horst Köhler. The “Ehrenmal” is dedicated to the more than 3,200 servicemen and women who lost their lives since 1955: “Den Toten unserer Bundeswehr. Für Frieden, Recht und Freiheit” (“Dedicated to the dead of our army for peace, justice, and freedom”). From the first plans until today, the Ehrenmal has raised criticism. While many people in Germany are afraid that “honoring the fallen” might revive the ghosts of the past, some others claim that German soldiers still do not get the appreciation they deserve.[20]

While many people in Germany are afraid that “honoring the fallen” might revive the ghosts of the past, some others claim that German soldiers still do not get the appreciation they deserve.

Germany is still searching for its new role on the global stage and struggles to build an identity as an international actor. In the United States, the impact of the war in Afghanistan on the country’s identity as a global actor will be limited. For Germany and the Bundeswehr, participation in the war will have a lasting impact for years to come. Eighteen years of war at the Hindu Kush have changed the Bundeswehr, which has gained merits in the field, as well as expertise and knowledge in fighting an asymmetrical war and conducting successful counter-insurgency operations. But limited successes are likely to raise skepticism in society at large when military operations are considered in the future. As the narrative of failure in Afghanistan is solidified in the collective memory, people will say, “Look at the poor results in Afghanistan,” and dismiss German participation in future large-scale military interventions.

Conclusion

Eighteen years of war in Afghanistan, what will remain? There is a chance that the war in Afghanistan will be remembered as a defeat, although the Taliban was never able to challenge coalition forces in a large-scale battle or force their retreat. Nevertheless, it seems that a narrative of failure will become dominant in the United States and Germany. This narrative is nourished by several mistakes. First was the underestimation of the complicated situation in Afghanistan. The coalition forces celebrated early military and humanitarian successes without securing gains, and so the hopes of the local populace turned into frustration and a breeding ground for later insurgency. Second, the decision to go after Iraq drew away resources that were needed in Afghanistan. Third, Afghanistan clearly shows the limitations of overwhelming military power in asymmetrical wars. Nearly two decades of war, and the most advanced military machinery, bankrolled by the wealthiest countries in the world, has produced a stalemate. The small wins and developments in Afghanistan are hardly recognized in the West. Afghanistan is in the news only when there are terror attacks and elections plagued by suicide bombings, corruption, and fraud. Based on these inputs, it is not shocking that, for many people, the coalition has lost the war in Afghanistan.

Regardless of the how Afghanistan will be remembered—failure or success, especially for Germany—Afghanistan will be a decisive mission going forward. Germany has not yet found its identity as a global actor, but fighting in its first war since WWII has left marks on the Bundeswehr and society. As the narrative of failure dominates collective memory, skepticism and objections to military interventions in complex situations will become stronger, making it even more difficult to convince the German public to send troops.

Supported by the DAAD with funds from the Federal Foreign Office (FF).

This report is based on research I conducted in Germany and the United States and reflects my preliminary results. The case study on the United States was done in 2019, especially the field work. This research is part of a larger project idea for which I am currently seeking funding.

[1] See, for example, Elizabeth A. Harris, “Amid Cheers, A Message: ‘They Will Be Caught’,” The New York Times, May 11, 2011; Dan Barry, “A Mix of Emotion Stored for a Decade,” The New York Times, May 2, 2011; “US President Barack Obama Hit at His Critics, Who Accuse Him of Not Being Decisive Enough, by Killing Al-Qaeda Leader Osama Bin Laden,” Al Jazeera, May 6, 2011.

[2] Simone Utler, “Wie Ein Richter Merkel Zur Räson Bringen Will,” Spiegel Online, June 5, 2011.

[3] SIPRI, Military Expenditure Database, n.d.

[4] Mary Papenfuss, “Lindsey Graham Says U.S. Should Consider Iran Attack That Would ‘Break Regime’s Back,’” Huffington Post, September 14, 2019.

[5]German Legal Code 90:286: Out of Area Missions; Matthias Bertsch: “Als das BVerfG Auslandseinsätze der Bundeswehr billigte,” Deutschlandfunk, July 12th 2019; William Tuohy, “NATO After the Cold War: It’s ‘Out of Area or Out of Business,’” Los Angeles Times, August 13, 1993.

[6] J. Baxter Oliphant, “After 17 Years of War in Afghanistan, More Say U.S. Has Failed than Succeeded in Achieving Its Goals,” Pew Research Center Fact Tank, October 5, 2018.

[7] “About Two-Thirds of Veterans Say the War in Iraq Was Not Worth Fighting,” Pew Research Center, July 9, 2019.

[8] “Rolling Thunder” has developed into a large event over the years. Thousands of bikers came to the capital every year to be part of it. But the costs to guarantee the safety and security for the bikers and the visitors were growing, too. Rolling Thunder, Inc. which was in charge of the ride since 1988, announced that 2019 was their last parade. In 2020, a new ride will be held, organized by AMVETS (American Veterans).

[9] “Todesfälle im Auslandseinsatz und in anerkannten Missionen,” Der Bundeswehr, July 24, 2019.

[10] “Vier Bundeswehr-Soldaten getötet,” Spiegel Online, June 7, 2003.

[11] “Afghanistan – ISAF (International Security Assistance Force),” Der Bundeswehr, January 5, 2015.

[12] Regierungserklärung des Bundesministers für Verteidigung, Dr. Peter Struck, zum neuen Kurs der Bundeswehr vor dem Deutschen Bundestag am 11. März 2004 in Berlin. [Statement by Federal Minister of Defense Dr. Peter Struck on the new course for the German Army before the German Bundestag on March 11, 2004, in Berlin.]

[13] Lars Gaede, “Das ist Krieg, Sergej, Krieg!” taz online, October 2, 2010.

[14] “Hier nimmt Minister Jung Abschied vom toten Soldaten,” BILD, May 7, 2005; “Ein Schmerz, der nicht vergehen will,” Cicero Magazin, n.d.

[15] Rudi Multer and Ludger Möllers, “Vor zehn Jahren starb Sergej Motz in Afghanistan: So geht es der Familie heute,” schwaebishe.de, April 29, 2019.

[16] Ulrike Demmer, et. al., “Rekonstruktion vom Kunduz-Anschlag: Ein deutsches Verbrechen,” Spiegel Online, October 6, 2010.

[17] “Anwalt der Opfer von Kundus hofft auf Europäischen Gerichtshof für Menschenrechte,” Welt Online, September 3, 2019. Nevertheless, Popal’s role in the process is not beyond all doubt, as German journalists found out. He dismissed the behavior of German soldiers in Afghanistan as arbitrary killings and fudged victim numbers. See Eric Beres, “Die ominöse Rolle des Opferanwalts Karim Popal,” ARD Das Erste, January 11, 2010.

[18] Martin Gerner, “Zehn Jahre nach dem Luftangriff von Kundus: Warum das Erinnern so schwerfällt,” Deutschlandfunk Kultur, September 4, 2019.

[19] For more information on the “Forest of Remembrance,” see https://www.bundeswehr.de/de/ueber-die-bundeswehr/gedenken-tote-bundeswehr/wald-der-erinnerung.

[20] Herfried Münkler, “Für die gute Sache,” Der Tagesspiegel, November 24, 2007; Stefan Reinecke, “Erzwungene Normalität,” Die Tageszeitung, September 7, 2009.