Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht

Kevin Ostoyich

Valparaiso University

Prof. Kevin Ostoyich was a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2018 and was previously a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2017. He is Professor of History at Valparaiso University, where he served as the chair of the history department from 2015 to 2019. He holds his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and his A.M. and Ph.D. from Harvard University. Prior to moving to Valparaiso, he taught at the University of Montana. He has served as a Research Associate at the Harvard Business School and an Erasmus Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently is an associate of the Center for East Asian Studies of the University of Chicago, a board member of the Sino-Judaic Institute, and an inaugural member of the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum International Advisory Board. He has published on German migration, German-American history, and the history of the Shanghai Jews.

While at AICGS, Prof. Ostoyich conducted research on his project, “The Wounds of History, the Wounds of Today: The Shanghai Jews and the Morality of Refugee Crises.” The Shanghai Jews were refugees from Nazi Europe who found haven in Shanghai, and thus escaped the Holocaust. For this project Ostoyich has interviewed many former Shanghai Jewish refugees and has conducted research at the National Archives at College Park, MD, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At Valparaiso University he co-teaches a course titled “Historical Theatre: The Shanghai Jews,” which fuses the disciplines of history and theatre. To date, students of the course have co-written and performed two original productions based on the history of the Shanghai Jewish refugee community: Knocking on the Doors of History: The Shanghai Jews and Shanghai Carousel: What Tomorrow Will Be. In addition to his work on the Shanghai Jews, he is currently working on projects pertaining to the experiences of ordinary Germans during the bombing of Bremen, German Catholic experiences in nineteenth-century Württemberg, German Catholic migration, and U.S.-German cultural diplomacy during the first half of the twentieth century.

Click here for an article by Ostoyich on the Shanghai Jews.

He is currently trying to interview as many former Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

Ida was terrified. She figured she would never see either her husband or brother ever again. For several days she fretted, not knowing what to do. While desperately trying to keep her own nerves together, she consoled her mother, who was in shock over having her youngest son taken away. But the fate of Albrecht and Sigfried was not Ida’s only concern. In the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht, the SS not only pressured the townspeople of Frickhofen not to have anything to do with the Jews, but also to deprive them of food.[1] Faced with the fear that her infant son, Harry, would starve, Ida begged for someone in the town to provide her with milk. Fortunately, one woman broke the barrier of fear and indifference in the town and started to sneak milk to Ida so she could feed her Harry. Having found milk for her child, Ida set her sights on getting her husband and brother out of Buchenwald.

Read the stories of other Shanghai Jews

Watch Kevin Ostoyich present these stories at an event in Cleveland.

Read about Kristallnacht Commemoration in Cleveland

Read about Event with Prof. Kevin Ostoyich

This article examines the lives of three women whose lives of comfort and tranquility were upended by the terror regime of National Socialism. Quite often narratives of discrimination and persecution under the Third Reich tend to be dominated by depictions of male experiences. For example, with respect to Kristallnacht, narrative descriptions tend to focus on the men who were rounded up and taken to concentration camps. Those stories are important and need to be told time and time again. So, too, are the stories of the women who were confronted by the loss of their fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons. We need to remember the challenges these women faced and the actions they took within the nightmarish atmosphere of the Third Reich in order to try to get their loved ones out of concentration camps while still looking after the rest of their families. On the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht, we remember women such as Ida Abraham, Auguste Sternberg, and Grete Gabler.

We need to remember the challenges women faced and the actions they took within the nightmarish atmosphere of the Third Reich in order to try to get their loved ones out of concentration camps while still looking after the rest of their families.

German Responses to Kristallnacht Anniversary

One Tough Seamstress

Who was Ida Abraham?[2] She was born Ida Rosenthal to Mina and Berthold Rosenthal on March 30, 1910. She had two brothers: Feodor, born in 1908, and Sigfried, born in 1919. She grew up in the small town of Frickhofen, which is not too far from Limburg an der Lahn. Ida had a comfortable upbringing and was very close to her mother and grandmother. The latter bought her a Singer sewing machine. Although Ida had some schooling in Frickhofen, her main education was from her mother and grandmother on the Singer. This was an education that would serve Ida well throughout her life. She married Albrecht Abraham in 1935. Albrecht, one of six children, grew up in Altenkirchen, and was a cattle trader. After they married, Albrecht and Ida lived with Ida’s parents in her grandparent’s house in Frickhofen. While Albrecht split his time trading in Frickhofen and Altenkirchen, Ida continued to sew. On March 15, 1938, Ida gave birth to her son Harry. This day that saw the arrival of her son, also saw the departure of Ida’s older brother, Feodor, for Palestine.

On the night of Kristallnacht, Albrecht was away on business in Altenkirchen. He was rounded up with other Jews and taken to Buchenwald. On that night in Frickhofen, a stone smashed through the window under which the infant Harry was sleeping. Meanwhile, Ida’s younger brother, Sigfried, was taken away to Buchenwald.

Ida’s father served in the German Navy during the First World War, and had visited Shanghai. After Ida had found her source of milk for Harry, her father told her he had been talking with friends about the possibility of escaping to Shanghai, because a visa was not needed in order to enter the city.[3] With this information Ida started to search for a way to get Albrecht and Sigfried out of Buchenwald and send them to Shanghai. She encountered people who had contacts in Frankfurt who were familiar with the process. One could leave Germany as long as one had a place to go. Due to the paper walls of quota systems and bureaucratic warrens, countries like the United States and England were off limits. Ida set to work, spending countless hours and taking multiple trips to Frankfurt. With money and perseverance, she secured the papers that indicated that Albrecht and Sigfried would be issued tickets to Shanghai, got the papers verified by the local magistrate, then had the papers sent to Buchenwald so that Albrecht and Sigfried could be released.

Harry notes, “She was a very, very determined and very, very involved type of individual. My father was on the quiet side. Not my mother. My mother was tough, hard-nosed, and sometimes difficult. [He laughs.] But that difficulty was what created the ability to accomplish what she accomplished.”

Upon Albrecht’s and Siegfried’s release from Buchenwald, Ida had only four weeks to get them out of the country, otherwise they would be sent back to the concentration camp. She now had to get the tickets that had been promised her. This turned out not to be easy. Those who had given assurances about issuing tickets now wanted more money. Ida turned to her father in order to use the influence of his non-Jewish friends to help apply the necessary pressure to make sure that those who had made promises kept them. The pressure worked. Then Ida needed to get the proper papers to allow Albrecht and Sigfried to take a train to Genoa, where they would board the ship to Shanghai. This too was not easy. Eventually, due to Ida’s efforts, Albrecht and Sigfried left for Shanghai.

With Albrecht and Sigfried on their way to Shanghai, Ida turned her attention to getting herself, Harry, and her parents to Shanghai as well. This led to friction, because her parents did not want to go. As a veteran and a prominent person in Frickhofen, Ida’s father did not want to leave. Despite this, Ida acquired the necessary permissions and tickets for all four family members to leave Germany and go to Shanghai. To this end, she gave up just about everything she owned save for her Singer sewing machine. After she made all the arrangements, however, Ida’s parents refused to go. According to Harry, “That really, really hurt my mother deeply.”[4] Ida and Harry left Germany with little more than the Singer sewing machine. Their journey to Shanghai took about six weeks.

In Shanghai Albrecht worked as a trader, Sigfried worked for a baker, and Ida, putting the Singer sewing machine to good use, became one of the most prominent seamstresses in the Jewish community. She even started to teach sewing to younger people.

During the war, the family lived in the Wayside Heim in the Designated Area that had been set up by the Japanese occupation forces. After the war the family started the process of applying for visas to go the United States. In 1947, Ida, Albrecht, and Harry left Shanghai for the United States, and Ida made sure her Singer sewing machine made the journey with them. They arrived in San Francisco. Given her sewing skills, Ida was immediately offered a job in a coat factory. Albrecht had more difficulty finding employment.

Thinking that the prospects for work may be better in Pittsburgh where they had friends, they moved there. Again, Ida was able to find work right away, but Albrecht could not. Then when the Abrahams went to Cleveland to celebrate Thanksgiving with family, Albrecht met a man at temple who offered him a job in Cleveland. Ida immediately found a job in a coat factory. Shortly thereafter she secured a job interview with Sears Roebuck. Harry accompanied her to the interview to act as interpreter, because neither Ida nor Albrecht spoke much English. Ida got the job and for the next thirty plus years, she was in charge of the production of slip covers for Sears Roebuck.

In 2003, Ida passed away at age 93.

Ida always remained a serious and determined person. Harry explains: “She was always haunted by the episode in Frickhofen. […] It just seemed to stick with her all the years, and in some ways she seemed to become tougher and tougher out of that, […] not so much with other people but with herself. […] She just took life as being very, very hard […] and really […] felt that this whole thing wasn’t fair. […] But the key to all of this stuff was that she wanted to make sure that the family was going to survive.”

“But the key to all of this stuff was that she wanted to make sure that the family was going to survive.”

Ida could never understand how it could be that people could let something like Kristallnacht happen. She could never fathom that people could deprive her and her son of food. Harry says, “That really affected her a lot. Going forward. […] In some ways [she had trouble] trusting people. […] I didn’t know her, you know, beforehand, but in talking with her brother [and others], they said she was a whole different person […] [and Kristallnacht] made her more tough and hard and difficult, as opposed to before that where she was fairly easygoing in temperament.”

Outside his office, Harry has placed something that always reminds him of his mother, something that goes deep into his mother’s history, something that accompanied her on her long journey from Frickhofen to Shanghai and then to Cleveland: The Singer sewing machine. The machine is there to remind us of one tough seamstress who worked so hard to bind her family firmly together. As Harry remembers, “She just loved to sew.”

Prized Possessions

Auguste Sternberg was born on November 24, 1894.[5] Her parents were Protestant Polish farmers in Lengoven. She had a younger sister, Annie, with whom she never got along well. They simply never saw eye-to-eye on anything. Her mother died of breast cancer while Auguste was still living in Lengoven. Auguste left Lengoven most likely after the First World War and found employment as a housekeeper for a wealthy orthodox Jewish family. In doing so, she became deeply knowledgeable in the religious practices of Judaism. Eventually she moved to Cuxhaven, where she met Hermann Sternberg.

Hermann was born on September 2, 1893, in Wetzlar an der Lahn to a very wealthy family of orthodox Jews who were cattle farmers. Hermann was somewhat of a black sheep and did not have much to do with his family. He served as a combat medic in the First World War and after saving an officer’s life under artillery fire, was awarded the Iron Cross.

Auguste and Hermann were married on September 29, 1930, in Cuxhaven. They then had two children, Ruth and Gerd (who now goes by Gary).

The Sternbergs lived in the downstairs of a very spacious house. Gary remembers it having a beautiful backyard with a rose garden, with a little creek running beside it. They lived very close to the North Sea and as such, it would get very cold during the winter, but overall Gary remembered loving Cuxhaven.

Hermann had his own orthopedic practice that he ran out of the house. He made artificial limbs, arch supports, trusses, and the like. The family was not wealthy but lived comfortably.

Gary remembers, “My mother was a very devout Christian, and she raised both me and my sister in the Christian faith, the Evangelical faith.” Despite Hermann not being very religious, Auguste made sure that the High Holy Days were observed in the house. She had only matzos in the house during Passover and made sure Hermann attended religious services. Gary remembers his family ordering their matzos because it was difficult to get in Cuxhaven. He remembers, “My mother probably knew more about Judaism than most Jews did even though she was Christian. […] My mother didn’t have a good school education but I think she was one of the smartest women [Gary chokes up] that I ever knew. She was just a hell of a lady.”

One day—Gary does not remember exactly when—the Nazis came for his father. The front door of the house had an oval glass inset that would rattle if there was a bang on the door. On that day he remembers, “early in the morning, it must have been four or five o’clock maybe—that’s when the Nazis did their best—they banged on the door and this glass [rattled], I mean like crazy. And we ran to the front door just in time to see them yank my father out. No goodbye, no nothing [about] where he was going, anything. Totally, just yanked him out of the house, dumped him on a truck with some other people and off they went. And it took my mother the longest time—it took her a month before she found out whether he was alive or not, where he was, how he was. It was horrible. And we had no other support. We used up the savings that we had. We used it up.”

And we ran to the front door just in time to see them yank my father out. No goodbye, no nothing [about] where he was going, anything.

Auguste frantically tried to figure out where Hermann was and what to do. Neither Hermann nor Auguste had family in Cuxhaven, so Auguste started contacting friends and Jewish organizations to try to figure out if anyone knew what had happened to Hermann and if anyone could help. After about a month, Auguste received a notice from the government that Hermann had been taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Soon thereafter, she received a letter from Hermann that he sent from the camp.

While Auguste was looking after her children, she started to get pressure from government officials to divorce Hermann since she was Christian. But as Gary explains, “She was a stout, devoted mother and wife, and she wouldn’t even hear of it.” He adds “that part alone makes her like a saint. Her loyalty to her husband was unrivaled.”

A wealthy woman named Mrs. Reinecke, who was a client of Hermann and a family friend, provided money to Auguste to use in order to get Hermann out of the concentration camp. Hermann had always been a personal hero to Mrs. Reinecke because she had acute problems with her feet and Hermann was the only person who could help her. Eventually, with the money supplied by Mrs. Reinecke, Auguste was able to get Hermann out of Sachsenhausen some seven or eight months after he had been yanked out of the Sternberg home.

Gary remembers his mother being intensely afraid and thinking that the Gestapo was spying on them: “My mother always thought that if you talked about anything against the government that they had people going around reading lips and that she’d be persecuted for talking against the government or even the kids talking against the government.” Gary remembers one instance in particular when they were sitting around the kitchen table after his father returned from Sachsenhausen: “My father started talking about the concentration camp, not in detail but generalities, [and] she quickly drew the curtains and said, ‘Hermann, you have to be careful because there are people out there, the Gestapo’s out there reading your lips!’”

Hermann and Auguste realized that they needed to get out of Germany. They went to the ship lines and found that there was only one passage available on the ship. Thus, they had the dilemma of deciding who of the four family members would go. Hermann insisted that Auguste go. But Auguste insisted that Hermann go because she felt that if Hermann stayed in Germany he would be killed. Gary explains, “So my mother won the argument, as usual, and he went on the Italian luxury liner.” While on the ship en route to Shanghai, Hermann took out the Iron Cross medal he had been awarded during the First World War and threw it overboard. As Gary explains, the Iron Cross had always been his father’s “prized possession.”

Now Auguste looked for a way to get herself, Gary, and Ruth to Shanghai as soon as possible. With Hermann already there, Auguste “worked like crazy to get passage” to Shanghai. She received help from the Jewish Joint. Meanwhile she looked for a job but had difficulty finding one because everyone knew that she was married to a Jew. The family’s funds were getting down to nothing.

Eventually, someone notified her to report to an upscale restaurant in a pavilion that overlooked the North Sea. It was a beautiful establishment. She went to the restaurant to apply for the job. The manager offered her the job without even asking for her qualifications. Auguste wondered how this was possible. She eventually found out that Mrs. Reinecke, the lady who had provided the money to get Hermann out of the concentration camp, owned the restaurant. Mrs. Reinecke had found out that Auguste needed a job and had set up the whole thing.

Gary explains, “This is how people worked […] Not all Germans were Nazis. There were some good people. [Mrs. Reinecke] could have jeopardized her reputation by helping a woman who was married to a Jew.”

In 1940, Auguste and the two children had to go to Berlin in order to make the arrangements to go to Shanghai. Auguste wrote a letter to her sister, Annie Kasulke, who lived in Berlin, about her predicament but did not expect her sister to respond given that they had never gotten along and had fallen out of communication. To Auguste’s surprise, Annie wrote back, offering to put Auguste, Gary, and Ruth up in her apartment in Berlin for as long as needed. They stayed in Berlin for two weeks and Annie “took wonderful care of us.” Meanwhile, Auguste worked on making the arrangements for the family to leave for Shanghai.

Annie had a Schrebergarten, a state-sponsored little garden outside the city with fruits, vegetables, rabbits, and three chickens. The chickens were her prized possessions, especially given the rationing of the war.

After Auguste finalized the arrangements for the journey, they prepared to go to the train. As the two sisters made their farewells, Annie handed Auguste a bag, and said, “Here, this is for if you get hungry on the trip.” Auguste did not look in the bag. Then while they were on the train and got hungry, Auguste finally opened the bag. In it was a roasted chicken. As Gary says, “So [Aunt Annie] took one of her prized possessions, one of her chickens, and gave it to us.” Gary chokes up and says, “I’ll never forget that.”

Upon arriving in Shanghai after a long journey through the Soviet Union and Manchuria via train, as well as a boat voyage on the Yellow Sea, Auguste expected to be taken to a place to stay, but instead Hermann took them to a restaurant where he and Auguste proceeded to have an argument because Hermann had neglected to find a place for them to live. Fortunately, they were able to secure a one-bedroom apartment. Gary said it was considered to be extremely luxurious because it had a W.C.—something rare in Shanghai and almost unheard of in Hongkew. Hermann set up a little workshop in a corner of the room for his orthopedic work. They made a meagre living. They had not been able to bring really anything with them to Shanghai, so they had to build up from scratch.

In 1943, the Japanese set up the “Designated Area” in the Hongkew district. This meant that the family had to move from their one-room apartment into a camp within the Designated Area. The camp they moved into was the Chaoufoong Road Camp, which used to be a former Chinese university. Gary and Hermann slept in bunks in the men’s dormitory and Auguste and Ruth lived in a large hall full of bunks. Gary explains the effect on his mother: “My mother went hysterical. There were bedbugs and lice, and it stunk. She went crazy.” Hermann was able to find a few weeks later a space on the third floor of what was referred to as the “hospital building.” The Sternbergs lived with four other families in a large one room that was divided only by bunks and sheets. They had communal toilets and communal cooking. Gary remembers that living in the overly-close quarters was not easy, with families often not getting along and kids screaming all the time.

After the war Hermann rented a little storefront on Chusan Road, and the family moved out of the camp into another one-room in a house on Tongshan Road. The lanes stank with garbage strewn all over the place, but Gary remembers, “that, by comparison, [it] was luxury.”

In June 1948, the family received their visas to go to the United States and were admitted on July 22, 1948. The family stayed in San Francisco for about three months. They then went to Cleveland. With a loan of $300 from the Jewish Joint they were put up in a spacious apartment. “We had two bedrooms, with a dining room, and a living room with a fireplace. Living it up! [Gary laughs.]” They were then allowed to go to the Salvation Army to pick out furniture. Gary remembers, “My mother was in her glory! She had a kitchen stove.” At first they had an ice box, but eventually they made their first major acquisition: a Westinghouse refrigerator from Mandel’s store. The family particularly enjoyed opening and closing the door because a light would come on. Gary explains that the refrigerator became “our prized possession.”

“This woman is no less a Jew than anybody here.”

Before marrying his wife, Gary eventually converted to Judaism. In 1964, Gary, his wife and daughter, and Auguste and Hermann moved to Los Angeles. Not too long afterward, Hermann passed away of lung cancer. Gary took care of the arrangements to have his father buried in Mount Sinai cemetery in the foothills outside of Los Angeles. Auguste had been taking care of Hermann and Gary believes the strain ultimately killed her, for just a year after Hermann passed, Auguste died of a heart attack. Gary faced some resistance as he made the arrangements to have Auguste buried next to Hermann in the cemetery. A rabbi led the funeral service for Auguste, and Gary remembers that during the service the rabbi noted how there had been some objections to a Christian woman being buried in a Jewish cemetery. Gary chokes up as he recalls what the rabbi said next: “This woman is no less a Jew than anybody here.” Gary says, “That was the truth. […] That was quite a statement.” Listening to Gary talk about the story of his family’s survival, about how his mother had always made sure to preserve and uphold her husband’s religion, about how she stood by her husband despite intense pressure to divorce him, and about how she got all of the members of the family safely to Shanghai, is clear that the memory of Auguste Sternberg is his “prized possession.”

The Story in Her Eyes

Born on November 21, 1909, in Vienna the first of four children to Isidor and Anna Prossnitz, Grete Gabler’s earliest memories were of card parties on Saturday nights with family and friends.[6] When she was just four years old, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were gunned down in Sarajevo and the world rushed to war. When she later looked back to the years of the First World War, Grete remembered being a hungry child, being fed on polenta, flour, and fat mixtures. Immediately after the war, she, along with many other starving children of Austria, was sent to the Netherlands. Although her father had initially been against sending her, he eventually was persuaded it would be best for the health of his ten-year-old child. Landing in Stadskanaal near Groningen, in a country where she did not speak the language, Grete was given a bath and then lined up with the other children to be selected by foster parents. A merchant family chose her and she went home with them. Not being able to communicate verbally with her family, there was awkward silence. Eventually, Grete struck upon a way to communicate and started to dance in front of the family. The ice broke and as she later remembered, she “had a lovely time there.”

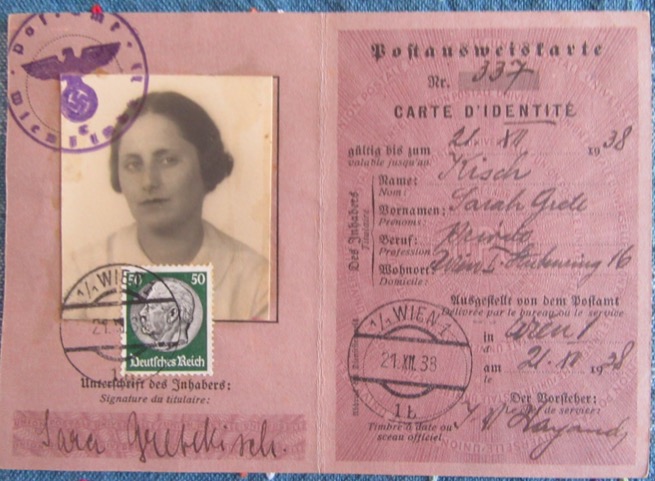

After spending half a year with a Dutch foster family, Grete returned to Vienna and attended the state school until she was fourteen years old. Then she went to a boarding school in Frankfurt am Main. After the war the Prossnitz family became quite wealthy, and her life became one of luxury: She later wrote, “There were balls and concerts and theater, there was the famous Vienna Opera. Every year we went for four weeks to Abbazia in Italy and afterwards to Baden by Vienna. In winter we went skiing. I had beautiful clothes and was very proud of my nutria fur jacket, when I was eighteen.” With her piercing eyes and gentle disposition, Grete attracted many Viennese suitors. Marriage proposal after marriage proposal came her way—but none with success until the dashing Walter Kisch came along in his tailored suits, elegant cigarettes, and two-toned shoes. As she remembered later in life, “Walter Kisch came on the scene, and I fell in love, and we got married.”

Grete and Walter were married in 1932. In 1937, Grete gave birth to their only child, Eric. The following year Germany annexed Austria. The family resolved to flee to Australia, but because of a recent incident involving the writer Egon Erwin Kisch in Australia, their application was denied despite their not being related to the writer. Then on the morning of May 29—Walter’s birthday—Walter was nabbed on the street by the Gestapo. His brother, Ernst, was also arrested that day, and the two were eventually sent to Dachau and then Buchenwald.

Grete later described what happened next:

“I gave up my flat and moved [in with] my parents. But not for long, as we had to leave there too and had to be content with a one-room-per-family [place] somewhere else. To get Walter out of [the] concentration camp (he was there for nine months), he had to have a visa to a foreign country. I ran from one consulate to another including the Japanese one, only to hear ‘Sorry, no.’ In the end the only sympathetic people, the Chinese, gave me one. Walter came out, but had to leave the country within three weeks. Where to get tickets for a ship? You had to get them from abroad, there was nobody to turn to. In [the] 12th hour, a business colleague of Walter’s father agreed to send one ticket […] from Holland, so off he went. I stayed on with my parents and for 11 months I was not able to leave. My parents had their permit and tickets to go to Australia when the war broke out. Now they had no chance to get saved. I was the last of my father’s children to go away, and my father could not take it, he [had] a heart attack and died. Now I had to take my mother with me. I was desperate to get the money for tickets to take us to Shanghai. We were forbidden to send telegrams or to telephone abroad. A good and sympathetic man at the American Express took pity on me and my desperation, and phoned my sister Emmy in New York. She, of course, having no money either, went begging and borrowing the amount and so saved mother’s and our [lives]. For the rest of my life I shall be thankful to her. Looking back, I see that these obstacles of not being able to go away made it possible for at least one of my father’s children to accompany his coffin, and I could take mother with me, who otherwise would have been taken to a concentration camp.”

Grete took her mother and Eric to Genoa and there in January 1940 they boarded the Conte Biancamano. Grete later described the bitter news that greeted her when they arrived in Shanghai: “The first thing [to happen] was that my brother-in-law, Dr. Ernst Kisch, who was also there, warned me that Walter [was having] a liaison with a married woman, which upset me [terribly].” Although the marriage was strained, the Kisches lived in comfortable accommodations in the French Concession of Shanghai at first given that they were running a lucrative leather goods store known as The Handbag. But when the Japanese set up the Designated Area, the Kisches were forced to move to Hongkew and endured deplorable conditions there. Disease was rampant in Hongkew and Walter became severely sick with dysentery. Grete remembered: “I did not want to send him to the primitive hospital in the ghetto, so I nursed him at home, observing strict hygiene. I washed my hands countless times, till they were sore.” She described the conditions under which the family lived at the time: “The business was gone, we had no income and started selling off possessions. I was busy fighting mold, bedbugs, and cockroaches. Walter tried to sell coffee, which did not even pay for his cigarettes.”

After the war, the family left Shanghai for Australia. They arrived in Melbourne in 1946. The marriage was broken. Grete remembered: “My marriage could not go on, my husband having constant affairs with other women. We got divorced. That was a great blow in my life. Now I was alone and had no money, but I had my Eric and that was worth facing life. I worked very hard day and night to support us and to pay half of Eric’s school fees.” Despite the financial difficulties Grete faced, she always made sure there was food in the home. Too much food, in fact. Eric remembers asking his mother why they always had so much just for the two of them. Grete’s response: After Shanghai she resolved that she and Eric would never be hungry again. After living as a single mother for many years, Grete met Arnold Gabler. The two married and were together until Arnold died from a heart attack. In 1960, Eric left for the United States, where he conducted graduate studies at Columbia University. The lure of the Big Apple was simply too great for Eric and he decided to stay. This was a great blow to Grete. She wrote “This broke my spirit and my health and I was sick for two years.” But Eric became very successful in the United States, got married, and fathered two children. Reflecting on the success and happiness of her son, Grete concluded her brief memoir with: “I see life from the good side.”

“I see life from the good side.”

When Grete passed away, Eric gave the eulogy at her funeral. His cousin, Peter, who had escaped the Holocaust on a Kindertransport, was unable to attend the funeral, so Eric sent Peter a printed copy of his eulogy. Peter then wrote back to Eric words that took him completely by surprise:

“I remember carrying her long veil at her wedding in the Seitenstättengasse Temple when I was only 4 years old! I remember sitting with her, you and my father on the day after ‘Kristallnacht’ in 1938 in her living room when some SA-bastards forced their way into the flat, threatening to arrest my father. Your mother had the presence of mind to somehow pay them off with some expensive knick-knacks in the apartment and they left without harming us, except having frightened us to our bones.”

Eric was dumbfounded.

Eric often speaks to congregations, schools, and universities about his family’s history. When he does so he always shows a picture that was taken right before Walter left Vienna for Shanghai.

Walter had just been released from his nine months of captivity in Dachau and Buchenwald, his hair was growing in from having been shorn, his face was puffy from the malnutrition he endured. Grete sat holding Eric on her lap. Whenever Eric shows the picture to audiences he points and says, “Look at her eyes, they tell the whole story.” Grete’s eyes told many-a-story to her son over the years, and yet until he read his cousin’s letter, he had never known of her presence of mind and courage in the face of the Nazis in the immediate aftermath of Kristallnacht.

On the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht, we should remember Ida Abraham, Auguste Sternberg, Grete Gabler, and the countless other women who persevered in the face of great obstacles and ultimately helped members of their families survive.

Professor Kevin Ostoyich is a Non-Resident fellow at AGI. He is associate professor and chair of the Department of History at Valparaiso University (Valparaiso, IN). His research on the history of the Shanghai Jews has been sponsored by the Sino-Judaic Institute (http://www.sino-judaic.org), the Wheat Ridge Ministries – O.P. Kretzmann Memorial Fund Grant of Valparaiso University, the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences, and Dean Jon T. Kilpinen of Valparaiso University’s College of Arts & Sciences. He is currently trying to interview as many former Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

[1] By this time there was only one other Jewish family in the town other than Ida’s.

[2] The “One Tough Seamstress” section is based on interviews of Harry J. Abraham conducted by the author on May 27, 2017 and October 27, 2018, as well as documents in Harry J. Abraham’s private collection. Fine-tuning of details was achieved through many conversations and e-mail exchanges.

[3] Harry notes that the food situation for the Jews in Frickhofen after Kristallnacht was a temporary one. Eventually, the family was able to get food again. The family never forgot the kindness of the woman who supplied Ida with milk. Harry returned to Frickhofen in 1976 and met the woman.

[4] Ida’s father’s service in the German Navy and prominence in the town ultimately did not save Ida’s parents from the horrors of the Holocaust. During the time of the Second World War, the Jews of Frickhofen and the surrounding area were rounded up and forced to do hard labor. Ida’s father was part of a group that was charged with clearing a forest. At his advanced age, the work started to cause him severe stomach problems. He then died while having an appendectomy. Ida and her mother corresponded via post through the Red Cross and Ida found out about her father’s death through a letter from her mother. Ida’s mother then went into hiding with her sister in a neighbor’s garage. They were eventually found. Ida’s mother was then sent to an extermination camp in the east and murdered.

[5] The “Prized Possessions” section is based on interviews of Gary Sternberg conducted by the author on October 28, 2017 and October 28, 2018, as well as items Gary Sternberg has donated to the Florence and Laurence Spungen Family Foundation. Fine-tuning of details was achieved through many conversations and e-mail exchanges.

[6] The “Story in Her Eyes” section is based on an interview with Eric Kisch conducted by the author on September 9, 2017 as well as the Grete Gabler’s unpublished memoir titled “Grete Gabler’s Story” which is in Eric Kisch’s private collection. Fine-tuning of details was achieved through many conversations and e-mail exchanges.